Visual Arts, and especially painting, suffer from the same dilemma that confronts writers of fiction: that is, a lack of specificity and clarity in defining its genres. When discussing painting, it is more common to think in terms of styles than genres, so we will call them that here. While fiction has dealt with the issue by coming up with dozens of genres and subgenres, painters have mostly tried to describe their work by fitting them into one of the existing groups art historians have used in the past.

The problem is that most of these descriptors are neither specific nor particularly descriptive. While “Impressionist” is well-understood, the term applied specifically to a small group of French painters who were thumbing their noses at the art establishment. The name, given by a journalist who was thumbing his nose in response, referred only to Monet’s Impression: Sunrise. Those in Monet’s group were thus dubbed Impressionist.

But what, other than appearing similar to a Monet, Manet, or Cézanne is Impressionist? How much more painterly than realistic must a work be before it is no long in the Realism style (or school, or bucket)? Delving into that level of discussion would take much more time and space than this single post, so let’s start by proposing how we can think of at least defining what these different styles are. Only then can we begin to discuss when a work moves from one to another.

To understand what I am proposing here, let’s think about genre fiction. We can readily think of Mystery Fiction as being different than Science Fiction. But what about Detective novels versus Police Procedurals? Are they fundamentally different in some way? We can begin to separate the genre into smaller genres—True Crime versus Mysteries—but you also run the risk of getting lost in all the specificity, like, say, Cozy Mysteries or Locked-Room Mysteries. And what about those books that straddle multiple styles? If a cozy mystery’s murder takes place in locked room, is that a new subgenre or two existing ones? Well, if you’re like the publishing industry, either you pick one and ignore the other, or you just claim you “don’t know how to market it,” and wait for your audience to get bored and dry up.

Let’s not wait for that to happen with painting. We can come up with our names for styles, understand how they relate to each other, and even (gasp) pick more than one when our art uses more than one style. More importantly, we can leave these definitions broad enough that artists don’t feel pressured into conforming to narrow, clichéd guidelines.

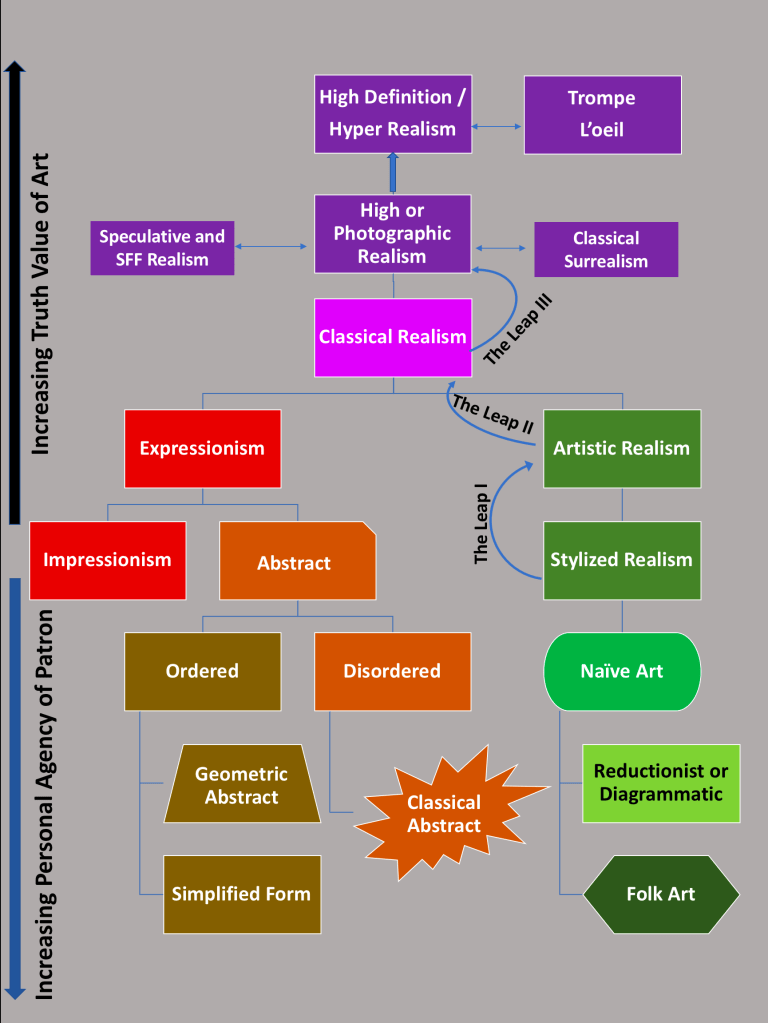

In Figure One, below, I have attempted, with some discussion with my artist wife, an initial graphical depiction of the broadest styles of art. A quick glance will tell you it isn’t all-encompassing, nor is it meant to be. Descriptions of These definitions aren’t meant to replace what historians are doing. They are for artists, enabling us to move forward and communicate what we’re doing to others without their having to get a MFA in Art History.

For now, let’s assume the color families represent broadly related groups of styles. There are groups of styles for which realistic depictions are critical, others that sacrifice photographic realism for artistic or stylistic depictions, and others that move further away from realism and more towards the conveyance of the feeling or an idea. In Figure One, these are purples, greens and warm tones (for no reason other than colors available in PowerPoint are limited and painting this thing seemed too much of a bother).

To understand the graphic, we start with the vivid magenta block entitled “Classical Realism.” I chose this as the starting block because this was the style in vogue when the Western world decided they’d invented art and knew exactly what it looked like. (Don’t get me started.) This the artistic style used by classical artists from the Renaissance period to the present in some of the more heralded art institution. It is characterized by real-life depictions of subjects while not losing sight of things like composition, color theory, and technique. Classical realism attempts to show the world not as it is, but as it would be if artistry could be found everywhere one looked.

Moving higher on the chart increases the Truth Value of the art, meaning it more accurately matches what can be perceived in reality. In terms of artistic styles, these higher truth values are usually demonstrated by the increased sharpness or focus of the piece. High Realism, also called Photographic Realism, for instance, attempts to paint the world as if the pigments were attached to a camera.

If we further increase the truth value, we reach what I am calling High Definition (HD) Realism. These painstakingly developed paintings and sketches attempt to perfectly reproduce an photographic image. However, unlike High Realism, where perfect accuracy can be sacrificed for artistic merit, HD Realism attempts to be only as artistic as a High Definition Photograph. These pieces depict life not only as we see it, but often in sharper detail than the human eye can perceive. For this reason, this style is also call Hyper Realism (or, as listed by the International Guild of Realism, as Super Realism). Trompe L’oeil (pronounced tromp loy) is a special kind of HD Realism wherein artists trick the viewer into seeing three dimensions on a two-dimensional space or canvas. It’s how we see three dimensions in real life from a 2D image on the back of the retina, so the brain is already primed to do this if the skill level is high enough.

Why do we make a distinction between this style and Photographic Realism? Because, as a photographer with over 50 years’ experience and one who has owned more than a dozen cameras, I can assure you that you won’t match the accuracy of these highly rendered photos with a typical camera. Expect to spend thousands on professional studio camera and lighting equipment if you want to match these kinds of results photographically.

Now, here I should say that as you increase the Truth Value of visual art, almost by definition are you decreasing the viewer’s Personal Agency in the work. Personal Agency here is the capacity of a person to make choices and decide on their own what an artistic work means and where it fits in the world. As artists become more high-end human printers, placing technique ahead of artistry, there is less interpretation for the art patron to do, and so s/he has less personal agency in the piece. Contrast that with someone who is viewing a work by Mark Rothko. To see more than color blocks requires the patron to engage with the piece and find a level of emotional interpretation. Perhaps what they see isn’t what Rothko thought he was painting, but that is the point. We all know what a pimple looks like; depicting what color energy wears takes more agency by the artist and the patron.

Painting reality takes tremendous skill. Adding artistry also takes skill, but adds an element of risk to the piece. There are equivalent adjuncts to High Realism that maintain its level of rendered accuracy, while adding imagination and thus risk. Classical Surrealism paints fantasy in a way that achieves physical realism. Were it a religion, Salvador Dalí would be its patron saint. Speculative or Science Fiction-Fantasy Realism paints purely or mostly imaginary subjects in photographic (or nearly so) manner. Comic books and Heavy Metal Magazine are examples of this style.

As we move away from realism and more towards artistic interpretations, we begin by separating into what I am calling Expressionism and Artistic Realism. Like many of these titles, Expressionism is not new. I can point to the dictionary definition: “a style of painting … in which the artist … seeks to express emotional experience rather than impressions of the external world.” Sounds good, but what does that look like? I have no idea. What I am advocating, therefore, is that we create separate style definitions that stray from Realism, but understand that the first step away requires artists to decide between holding onto some degree of realism and wholly rejecting the Classical school and painting what is felt.

So, Expressionism here is more of a catch-all (genre) than a style (subgenre). It in turn splits into Impressionism, which any long-term lover of painting understands, and Abstract painting, equally understood. Impressionism paint artistically rendered impressions of a subject while still holding onto its basic form. Abstracts can be inspired by real-life objects, but paint what the artist felt about it rather than the shapes s/he saw.

There is a well-known term, Post-Impressionism, but I ignore it here because I believe it serves more to separate those who attempted to paint in an Impressionistic style from the small group of painters who started the movement. Here, thus, it isn’t an artistic distinction, but a historical one. And, given the father of Post-Impressionism, Paul Cézanne, was an Impressionist, I’m calling the whole thing bollocks. I shall call any piece painted in an Impressionistic style as Impressionism. Whether it will be masterful, good, or bad Impressionism is a separate matter. Here, we are talking not of quality of work but choice of style. Hey, Messrs. Van Gogh and Gauguin, you’re in the club!

Abstract art can be further separated into what I call Ordered versus Disordered. Ordered abstracts can be Geometric (e.g., Rothko) dealing largely with shapes or Simplified Form abstracts, in which items are reduced to abstraction through simplification. Here, the painter’s camera lens is so blurry, you are no longer sure what the subject was, but you can guess and you can feel something about the art. Disordered Abstracts are wherein the artist runs free, as did Jackson Pollock and Joan Miró. They don’t paint things; they paint feels.

On the right side or the diagram, Realism is reduced to what I call Artistic Realism, which itself can be a broad range. At its high end, you have the works of J.M.W. Turner, John Singer Sargent and Edward Hopper, who were not painting the world as it was. They were painting it as it should have been. Sunsets should be ashamed of themselves for not looking like a Turner painting. Sargent painted beautiful portraits that sometimes looked more like each other than the subject, and that’s fine! And you haven’t been lonely until you’ve been properly Hopper Lonely.

Moving further away from Realism and more towards high-end cartooning takes us to Stylized Realism. (Note: I will punch in the face anyone who claims “cartoon-like” is an insult. Stylized Realists include some of my favorite artists, like Archibald Motley, Amadeo Modigliani, and Ernie Barnes. They had a style, and it worked. More many novice artists, this style is defined and limited by technical skill. However, for skilled artists, how their art is stylized can be a choice. Motley, for one, could paint any damned way he pleased. Skill allows for choices.

To be clear, depicting the world realistically takes Skill with a capital S. Moving up along the graphic towards increasing Truth Values takes artistic refinement. Thus, moving from Stylized Realism to Artistic Realism takes what I am calling “The Leap.” Think of your favorite Sport wherein a young player suddenly becomes a starter or an All-Star. S/he has taken The Leap. The same applies to Art and everything else. It takes skill and practice to achieve Artistic Realism, and it’s much easier to move down the chart than to move up. The Leap is where your style ceases to be defined by limitations in your skill level and becomes merely a choice for that piece.

It should be said here that moving from the lower end of Artistic Realism (where most of my recent work sits) to the high end requires a second Leap. For less-skilled artists, Artistic Realism is very likely as close to depicting reality as we can manage. For masters of the style, like Turner, there is no limit. They paint how they wish to paint. A third Leap occurs between Classical and High Realism, driven mostly by repetitions. In order to know what to paint, you must first learn what not to paint. That takes time. I don’t believe there is a fourth leap from High to HD Realism. That requires only OCD, coffee, and too much spare time. (Not a fan.)

Moving down the chart again, we reach Naïve Art (a la William H. Johnson, Henri Rousseau) and Reductionist (like Cubism or Jean-Michel Basquiat) or Diagrammatic Art (Keith Haring). The lowest shape on the chart is Folk Art, which again can be a broad range of skill levels, but is mostly marked by the artists’ caring less about fitting into one of the styles listed above and more in depicting personal or cultural stylistic elements. While formal definitions of Naïve Art lump in new, untrained artists, I call that folk art, as many skilled artists paint in a naïve style on purpose.

There are likely things missing, as this is a first draft, but I believe it’s a start. One might question, for instance, “Where does Andy Warhol’s art fit in?” And other than the rubbish bin, I’m not entirely certain. One can certainly argue it’s between Stylized Realism and Naïve Art, but that brings up my final point. As in literature, individual art doesn’t fit neatly into single boxes. A piece can mix styles on purpose (or by happy accident) and that’s alright. We can present the work as a High Realism / Impressionism piece and no Art Popo will come and get us. If we are brand-spanking new, we can paint Folk Art in a Naïve style, and no one will start a war to get you call it one or the other. All I really advocate, in the end, is that we get on the same page and stop being wedded to hackneyed descriptors that don’t really mean anything.

Radical, right?

Let me know what you think in the Comments. Cheers for reading.